Women To Read is a monthly column from A.C. Wise highlighting female authors of speculative fiction and recommending a starting place for their work.

Welcome to October’s Women to Read. This time around, I have three short stories and a novel to recommend. Two of my recommendations are science fiction, while the other two are appropriate to the Halloween month: one, an alternate history with a horror twist, the other, horror with a historical vibe.

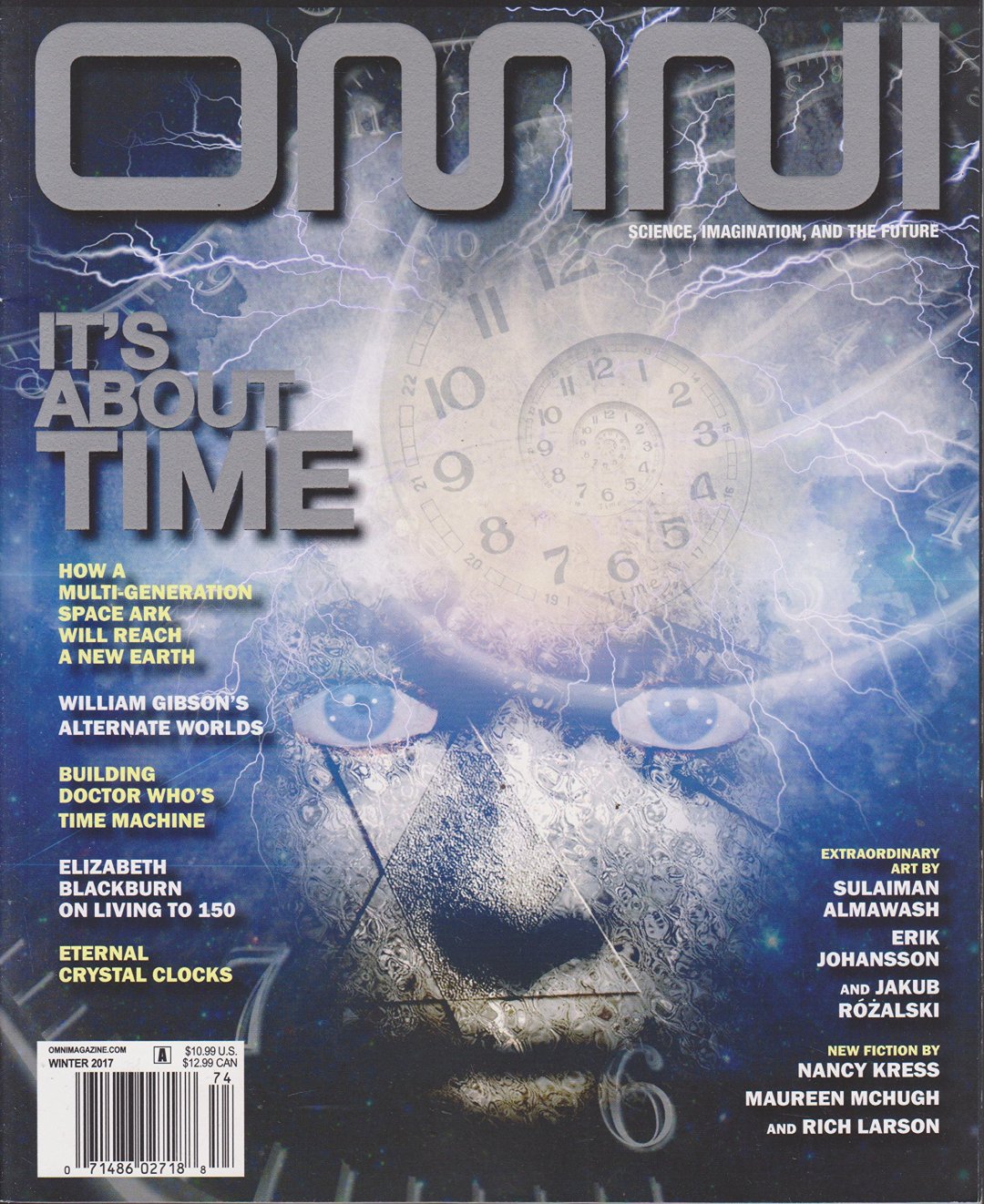

Nancy Kress is a multi-award-winning author with a vast body of work. The piece of hers that most recently caught my eye is “Every Hour of Light and Dark”, originally published in the newly-revived Omni Magazine, and reprinted in The Best Science Fiction of the Year Volume 3.

In the future, humanity has colonized the moon, and professional art forgers work with scientists to rescue treasures from Earth’s past, bringing them forward in time and leaving copies in their place. Cran is part of this team, but laments that he will never create anything original or truly beautiful like the great masters. He can appreciate true beauty however, and becomes obsessed with a Vermeer painting, Lady Sewing a Child’s Bonnet.

The light! It falls on the figure, a woman bent over some sort of sewing. It glows on her burgundy gown, on the walls, on a pearl necklace lying on a table. Almost it outshines the soft glow of the Square itself. The woman seems sad, and so real she makes Cran’s heart ache.

He decides he must have it for his own, and plans to steal it and replace it with a copy made by his colleague, Tulia. However, the transfer goes wrong, and Tulia’s forgery ends up in Vermeer’s time, while the original ends up in 2018 in the National Portrait Gallery, appearing next to Tulia’s forgery which the art world has assumed for centuries now to be an original Vermeer. The new painting is tested, discovered to be less than 10 years old – its age when Cran stole it – dismissed as a fake and relegated to storage. There, Cran is eventually able to retrieve it, passing it off as a forgery in his own time as well, with only Tulia realizing what he’s done.

With this story, Kress asks interesting questions about authenticity and value. The value of art is frequently what someone is willing to pay for it, or what a group of experts mutually agrees its value should be. But is there any inherent value? Is the exact same arrangement of paint on two different canvases worth more depending on the hand that applies it? Tulia’s work is indistinguishable from Vermeer’s, and due to the vagaries of time travel it is older and carries the provenance the true work does not. So what is authentic? What is real? Kress asks the reader to consider whether there is such a thing as objective value, or whether beauty and worth are truly in the eye of the beholder. Amidst these questions, she also delivers a satisfying story, and growth for her characters.

Justina Ireland is an author and an editor, and my recommended staring place is her latest novel, Dread Nation. I know one isn’t supposed to judge a book by its cover, but this one had me immediately hooked, and the contents did not disappoint. Set in an alternate past where the Civil War ended not with peace, defeat, or surrender, but because the undead rose, the story follows Jane McKeene, a young woman enrolled at Miss Preston’s School of Combat for Negro Girls. There, students learn to put down the undead, not as a means of self-defense, but so one day they might be hired as Attendants to protect society’s fine white women.

Even in a world plagued by zombies, black bodies are the first on the line, while whites cling to the illusion of an America that no longer exists. Politicians claim big cities like Baltimore – where Miss Preston’s is located – are safe, despite mounting evidence to the contrary. Jane is smart, an excellent fighter, near the top of her class, but frequently clashes with authority. She knows Baltimore isn’t as safe as those in power would like to pretend, and she’s proven right during a horrifying public demonstration of a vaccine that its inventor claims makes Negroes immune to the zombie virus. When all hell breaks loose, Jane steps in to save the audience, including the Mayor’s wife. Her heroics result in an invitation for her and another Miss Preston girl, Katherine, to one of the Mayor’s dinner parties as Attendants.

In Jane’s eyes, Katherine is stuck up; in Katherine’s eyes, Jane is infuriating with her flaunting of the rules. They constantly get under each other’s skin, but fate forces them into an alliance when they stumble on one of the Mayor’s secrets and they’re sent into exile in Summerland, a supposedly ideal town out west surrounded by a massive wall keeping out the undead.

The novel is brilliant, fast paced, and brutal. It deals in ugly truths about race, class, and gender, and delivers emotional gut-punches as Jane and her fellow students are forced to put down dead friends and family members in order to survive. Ireland threads loss throughout the novel, in Jane’s present and in her past. Each chapter in the first section is headed by an excerpt from Jane’s letters to her mother back home, who she fears she will never see again.

My one regret about leaving Rose Hill in such haste all those years ago is that I feel like I never got to give you a proper good-bye, Momma. I know how you sometimes see fit to hold a grudge. I hope your lack of letters isn’t tied to you being in a fine temper. It’s hard to apologize when the miles steal ever last bit of affection.

What is said and what goes unsaid in the letters is beautifully done, and Jane’s voice comes through most strongly when she’s putting a rosy face on the horrors of her daily life. The slow unfolding of Jane’s history, and her complicated relationship with her mother, is wonderfully handled, as is Jane’s relationship with Katherine – growing from antagonism to grudging respect to genuine friendship. Jane herself is stubborn and fierce when she needs to be, but also utterly human – allowed to be flawed, afraid, and lean on her friends for strength.

Dread Nation reads compulsively. It’s one of those novels I didn’t want to put it down, but at the same time didn’t want to finish because I wasn’t ready for the story to end, or to leave the characters behind. Immediately upon reaching the last page, I looked up whether there would be a sequel. To my delight, there will be, but with that said, Dread Nation stands well in its own. If the story ended with one book, I would be sad, but still perfectly satisfied.

Sarah Grey is a California-based author, and my recommended starting place for her work is “A Bond as Deep as Starlit Seas” published at Lightspeed Magazine. The bond of the title is between a captain and her starship, and Grey writes it beautiful, imbuing the relationship with a real depth of emotion.

Cleo isn’t just any starship. She’s a near-obsolete Juno-class cargo ship with emotive-adaptive capability. But more importantly, she is Jeri’s ship, her companion, her partner, and they’ve been together for years. Cleo knows when and how to adjust the temperature to Jeri’s liking; she suits the wall displays to Jeri’s moods; she anticipates their next adventure and chooses the best flight paths without Jeri having to say a word. Jeri knows better than to give her up, but she can’t deny the financial sense of it of trading her in for a newer, faster ship. She reluctantly agrees to sell Cleo on one condition – that Cleo never be broken down for scrap.

“I won’t sell, then.” She imagines Cleo picked apart, her ruby-red dermal buffer peeled back, her carbocine shielding sliced away, her titanium skeleton laid out, bare and pale, in the ghost-white light of the distant Nikutan sun. She heaves the slate toward Abbess Ocala. “If she’s headed for scrap, I won’t even negotiate.”

It’s the best compromise Jeri can think of to keep herself from having to work for the rest of her life, but she’s still filled with doubt and immediately regrets her choice. Her doubts are quickly justified as she learns that the Henza temple where she sold Cleo is notorious for making deals full of loopholes that work solely in their favor.

Grey’s use of language throughout the story is gorgeous, and as mentioned, the bond between Jeri and Cleo is palpable. It’s impossible not to root for them. The story plays effectively with the tropes of a trickster tale. At the end of the day, it’s a deal with the devil story, where the clever hero must outthink a foe who specializes in stacking the deck. The setting is wonderfully realized, and the world feels rich and lived-in. I would happily read more stories set in this universe should Grey be inclined to write them.

Nibedita Sen is a NYC-based author and editor, and my recommended starting place for her work is the unsettling “Leviathan Sings to Me in the Deep” published in Nightmare Magazine.

The story is written as a series of entries in the journal of a whaling ship captain. Despite sailing in overfished waters, two months into the journey, the ship encounters its first whale.

When the cow rose to surface, the harpooners fired cold irons into the soft flesh of her blubber-sides and she expelled a great mass of blood and foam from her spout. The boatheaders let out the smoking lines and made them fast as she dived again, but one man was caught around the thigh by the line, instantly shattering the bone, and pulled into the sea.

Shortly after the cow is killed, her calf is spotted. The First Mate claims to hear an eerie, crying noise, but the captain dismisses it. The unsettling crying continues, and the calf follows the ship, until one of the crewmen can’t bear it anymore and kills the calf, even though doing so is considered bad luck. Meanwhile, Glass, a scientist traveling with the ship, becomes obsessed with an organ recovered from the whale’s head, which he believes is the key to their song. By studying it, he believes he can reproduce their method of communication. He is able to rig up a strange instrument that produces a kind of singing, but the music has an unintended effect on the crew, and the sea itself.

Sen perfectly captures the tone one would expect to find in a whaling captain’s log, giving the story the feel of a classic piece of literature like Moby Dick. At the same time, the uncanny and the weird are threaded throughout, and there is a creeping sense of dread and wrongness suffusing the whole thing. Science, horror, and practicality clash to drive the plot forward – many of the crew are simply trying to make a living, Glass expects to make a discover that will rock the scientific world, and the whales are a force of nature with an agenda of their own. The story has an eco-horror/weird-punk feel, making it somewhat reminiscent Dan Simmons’ The Terror, Jeff VanderMeer’s Area X trilogy, and even Catherynne M. Valente’s Radiance, and yet “Leviathan Sings to Me in the Deep” is wholly its own. As with Grey’s story, I would happily read more work set in this world if Sen were inclined to write it.

1 Comment

Women to Read: October 2018 – Headlines

October 18, 2018 at 7:56 am[…] post Women to Read: October 2018 appeared first on The Book […]